Australia is considering softening its opposition to investor-state dispute settlement (#ISDS) in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), according to Primrose Riordan of the Financial Review.

This topic is one of the sticking points in the stalled negotiations, alongside more traditional trade concerns like dairy market access.

Further complicating the talks is the sheer number of negotiating partners. Twelve countries are involved in the talks. Many of them – like the US, Canada and Mexico – already have preexisting trade and investment deals of their own.

But there are gaps in the coverage. For instance, while the US and Australia have a trade deal, it does not permit investors from each country to directly challenge the other country’s regulations in arbitration tribunals.

How much would the TPP further integrate investment governance in the Asia-Pacific region?

To get a sense, I compared the country pairs at the TPP talks that already allow investor-state dispute settlement between them, versus those that would newly allow it under 12-way integration. The first figure here is the “before” picture, which I constructed using UNCTAD’s data on investor-state agreements.*

At the moment, only 35 country pairs have treaties.

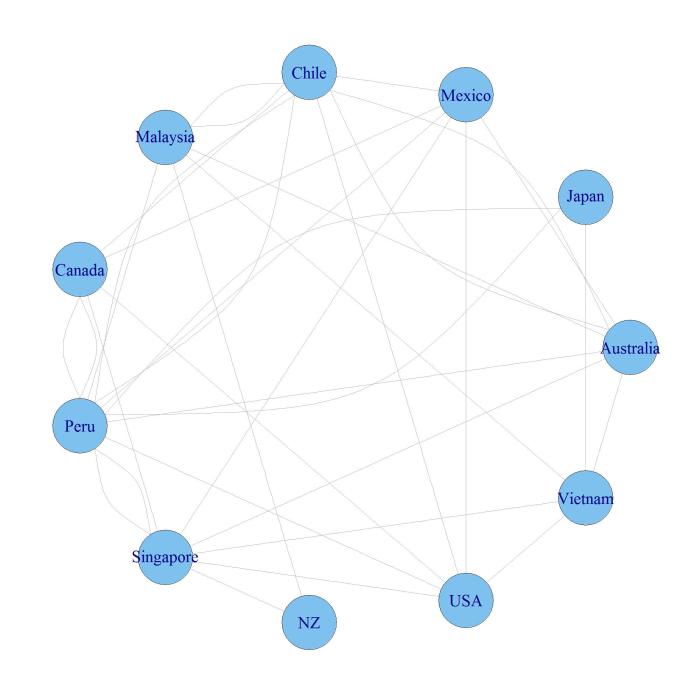

Here’s what the graph would look like after 12-way integration:

The “after” picture is much more integrated. Indeed, we would nearly double the number of bilateral treaty equivalents to 66.

While treaty negotiators think in terms of the number of country relationships cemented, this is not the most useful way of thinking about investor-state disputes. Clever investors can already figure out ways to game the status quo. As Sergio Puig writes, investors have tactics at their disposal to milk the network for all it is worth, including forum shopping, party shopping, relief shifting and more.

For example, a US investor could attack an Australian regulation by registering a Peruvian subsidiary and going through that. This despite there being no Australia-US investment pact. According to the World Bank’s rankings, it is as quick or quicker to get a business registered in many TPP target countries as it is in the US. So this type of nationality planning is not far-fetched – especially for a big enough dispute that might justify the re-registration transaction costs.

In short, the TPP would make certain disputes easier. They could be launched with less shopping around. But the basic architecture making these disputes possible is already in place.

++

*I used only those agreements UNCTAD listed as investment treaties (or trade pacts with ISDS). This metric might overstate the number of current treaties. Jason Yackee, for instance, has suggested UNCTAD’s statistics do not always clearly distinguish between pacts that have and don’t have ISDS. I excluded pacts labeled as TIFAs or EPAs, which do not typically grant investors standing.

3 thoughts on “Integrate U”